What Was Required, and Why It Mattered

Truncheons specification

Long before anyone talked about “standard issue” truncheons, the British War Office had already tried to define exactly what one should be.

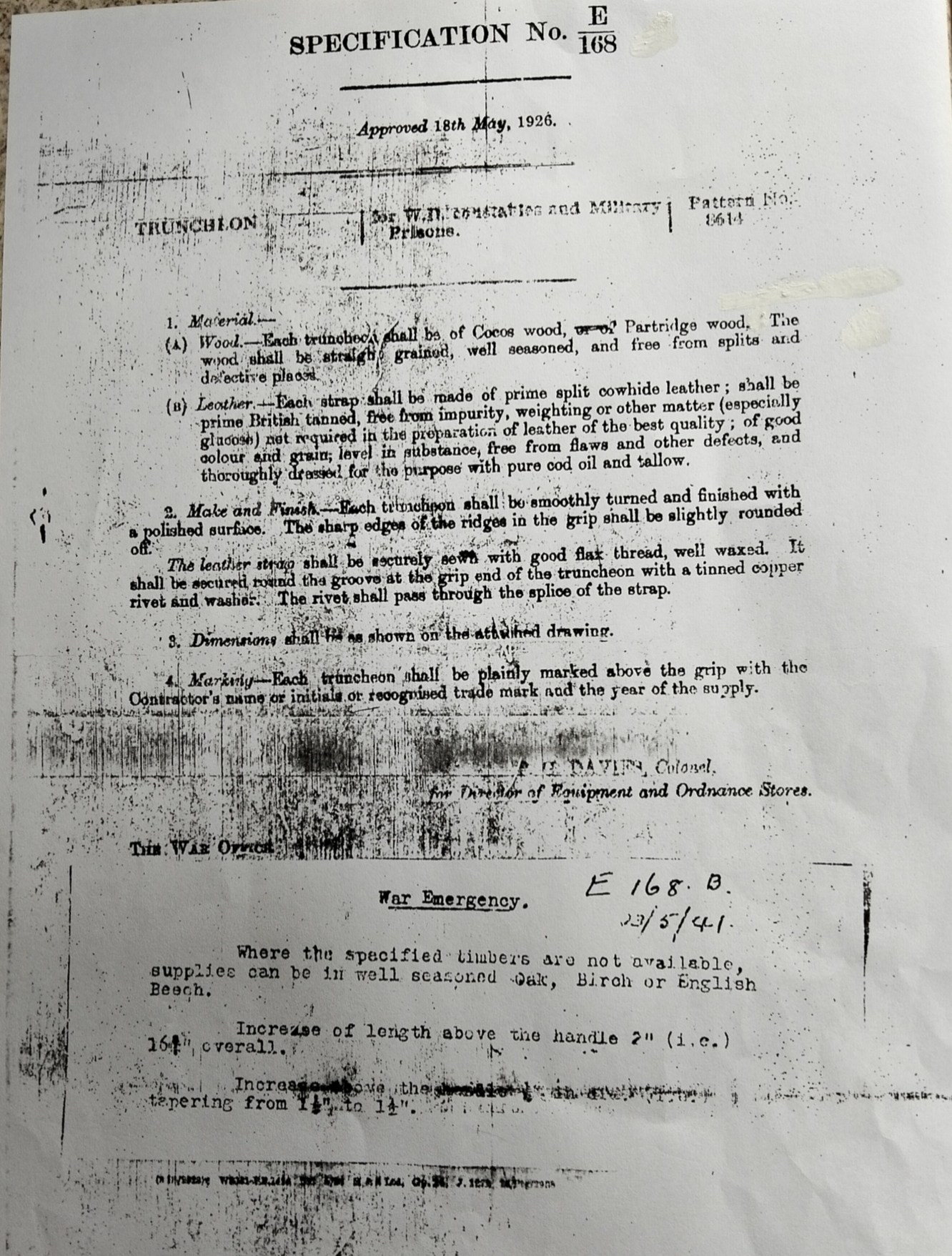

In May 1926, the War Office approved Specification No. E168, formally covering “Truncheons for War Department Constables and Military Prisons”. This document is not a guideline or a suggestion. It is a proper procurement specification, spelling out materials, dimensions, finish, markings, and even how the leather strap was to be made.

It matters because it shows two things very clearly:

- There was an official standard on paper.

- Even at this early stage, that standard allowed for more variation than most people assume.

Why a Specification Was Needed at All

By the mid-1920s, the War Department Constabulary and military prison staff occupied an awkward space. They were not civilian police, but neither were they front-line soldiers. Their equipment needed to look official, be robust, and comply with centrally approved stores regulations.

The truncheon was treated as controlled equipment. It was issued, inspected, and accounted for. A formal specification ensured that suppliers delivered something consistent enough for service use, rather than relying on local improvisation.

The Approved Materials

The 1926 specification is unambiguous about wood choice. Each truncheon was to be made from:

- Cocos wood, or

- Partridgewood

Both are dense tropical hardwoods, chosen for strength, resistance to splitting, and the ability to take a clean turned finish. The document also specifies that the timber must be straight-grained, well-seasoned, and free from splits and defective places.

That alone tells you something important. The War Office was not interested in cheap, easily available timber. Durability and consistency were prioritised over convenience.

Dimensions and Weight

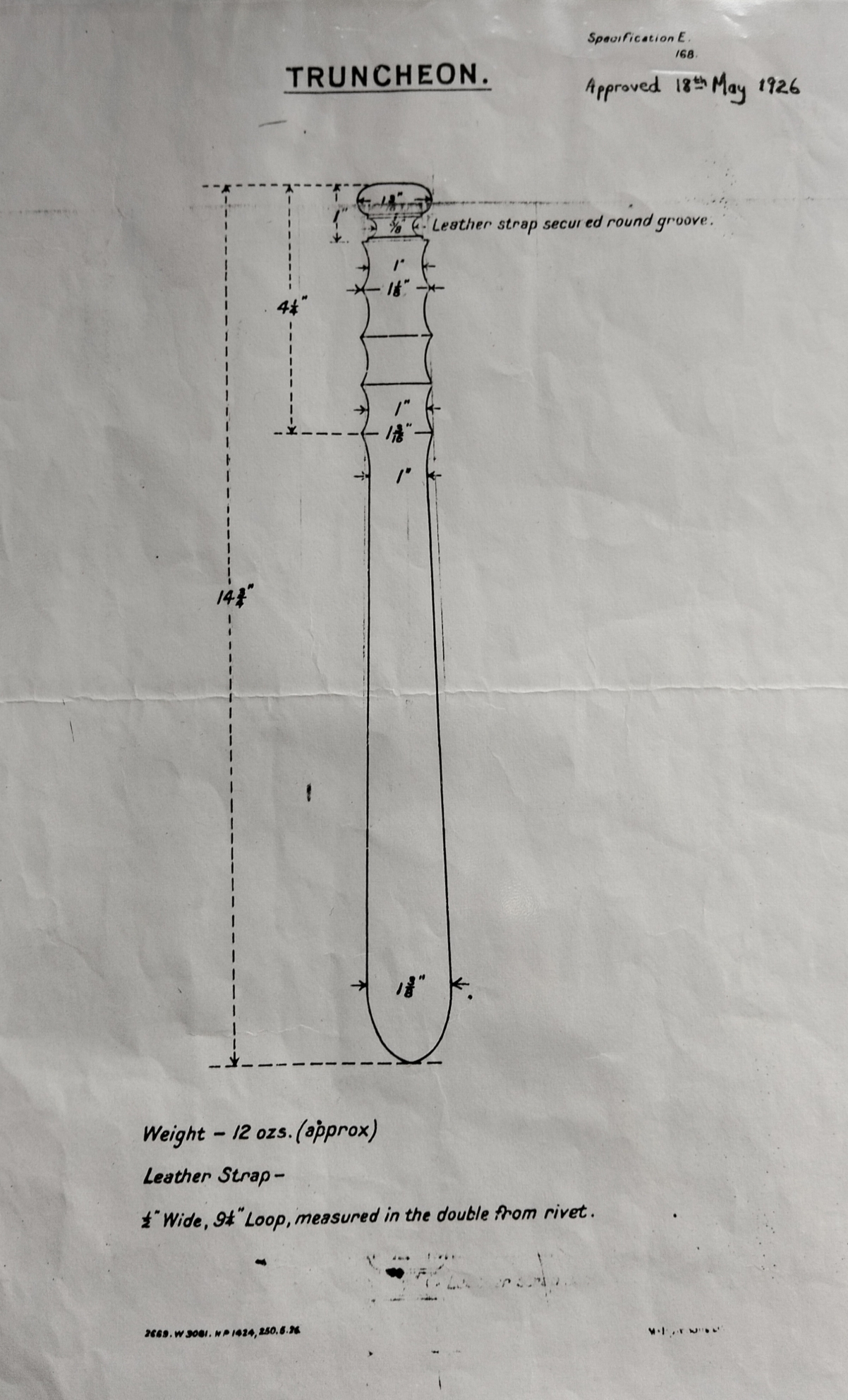

The standard truncheon defined by the specification is not especially long by modern standards. The document sets out the following:

- Overall length: approx. 14½ inches

- Length of grip: approx. 3¼ inches

- Diameter at thickest part: approx. 1⅜ inches

- Diameter at hilt: approx. 1⅛ inches

- Weight: approx. 12 oz

This places it firmly in the category of a compact but purposeful baton, rather than the longer, heavier patterns many people associate with later uniformed police use.

Make and Finish

The specification is unusually precise about finish, which tells us how these items were expected to present.

Each truncheon was to be smoothly turned and finished with a polished surface. Even the details of the grip were controlled, with the sharp edges of the ridges to be slightly rounded.

This was not crude equipment. The finish mattered, both for handling and appearance.

The Leather Strap (Thong)

The leather thong receives almost as much attention as the wooden body.

It had to be made from prime split cowhide leather, British tanned, free from impurity and weighting, and of good colour and grain. The strap was to be properly dressed for the purpose with pure cod oil and tallow.

The strap was to be securely sewn with good waxed flax thread, and secured at the grip end of the truncheon with a tinned copper rivet and washer, passing through the splice of the strap. It was also to be seated into the groove at the grip end, so it sat properly rather than flapping about.

This level of detail reflects how seriously the War Office viewed retention and durability. A failed strap was not acceptable.

Marking and Accountability

Each truncheon was required to be plainly marked above the grip with the contractor’s name or initials, or a recognised trade mark, and the year of supply.

This is crucial for collectors today. These markings were not decorative. They were mandated for traceability.

What This Specification Does, and Does Not, Tell Us

What the 1926 specification gives us is a baseline, not a promise of uniformity forever.

It tells us what the War Office wanted, what materials were officially acceptable, and how truncheons were meant to be finished and identified.

What it does not tell us is which firms supplied them in practice, how strictly materials were adhered to over time, or what happened when approved timbers became unavailable. Those questions only arise later, particularly during wartime, and they deserve separate treatment.

Why This Document Still Matters

This single specification undercuts a lot of modern assumptions.

It shows that even at the point of formal standardisation, variation was already built in. Two different woods were approved from the outset. Finish and marking were controlled, but supply was distributed.

Understanding this document properly is essential if you want to make sense of why surviving War Office and later Ministry of Defence truncheons show such diversity today.

If you want a traditional British police-style wooden truncheon, we sell a replica of a 1960s Leeds City Police issue, complete with leather lanyard, at a very reasonable price.

Click the button below to find out more.